Agarwood has long been appreciated for its multipurpose uses, range from incense for religious and traditional ceremonies, perfume, medicine and ornamental functions in many countries. The occurrence of this-so-called the wood of the gods has been strongly surrounded by myths and history. Agarwood use is mentioned in the Old Testament as ‘aloe’ or ‘ahaloth’ in Isalm 45:8. Agarwood is the only tree in the Eastern myth that has been descended to Man from Eden garden (Duke, 2008). In Egypt and Japan, Agarwood was used to embalm dead bodies. In India and Cambodia, it is used for traditional and religious ceremony.

The resin compound of agarwood is highly commercial. Resin impregnated in the heartwood a number of agarwood-producing species is due to fungal infection. Two mostly known genera are Aquilaria and Gyrinops that are native to Southeast Asia with India,Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Laos and Papua New Guinea being the main producing countries, and Singapore being the central trade country (Persoon, 2007).

Agarwood is used to make Great and Beautiful Agarwood Carvings/Sculptures.

Agarwood Beads made from grown-up trees is another area of its usability. In some Religions, they believe that wearing The Agarwood Beads can keep you safe from The Evils Spirits and Bringing Good Luck. The Agarwood is also named “The Wood Of Gods”.

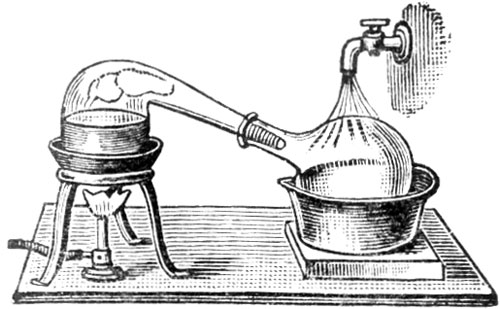

The Agarwood Oil is The most expensive essential oil of it’s kind. It has been known and used as natural, non- alcoholic perfume known as Oud or Dehnul-Oud. Each different area of Agarwood produces a different fragrance of aromatic smell. The Agarwood Oil is distilled from the cheaper quality of Agarwood and the yield is very low between 0.0002 % up to 0.010% depends on the raw materials and the Agarwood itself. That is why the price of The Agarwood Oil is expensive.

Agarwood Incense available in cones, coils or sticks made from Agarwood are using for Aromatherapy & Religious Usages.

Natural forests have been the main resource for agarwood collection for many years. However, agarwood hunters usually cut down the whole trees to find the resin and this practice has diminished agarwood population in the wilds and consequently has led agarwood-producing tree species under a threat of extinction. Major harvesting of agarwood was recorded between the 1980s and early 1990s in East Kalimantan caused by high demand for gaharu and was due to diminishing supply from countries like Vietnam and Cambodia (Barden et al.,2001 in Gunn et al., 2003). This excessive hunting activity has caused significant reduction of wild agarwood stocks within a short period of time. Similar activity also occurred in Papua after agarwood hunters landed in 1996 that has led to an ending of agarwood harvesting from its natural habitat (Persoon, 2007). 1998 was the first officially recorded year for agarwood discovery and harvesting in Yapsiei, May River and Ama villages in West Sepik, Papua New Guinea (Gunn et al., 2003). Harvesting of agarwood in these countries involve professional and traditional collectors. Professional collectors sponsored by Chinese and bogus trades were sometimes dropped by helicopters to hunt for agarwood (World Wide Fund for Nature, 1999).

In November 1994, Aquilaria malaccensis Lamk. was initially listed in CITES (the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna), Appendix II to prevent this species from extinction. However, continual excessive agarwood exploitations have then put two genera Aquilaria and Gyrinops in CITES, Appendix II, only ten years later. CoP13 Prop.49 (TRAFFIC, 2004) listed 24 species of the genus Aquilaria and seven species of the genus of Gyrinops. CITES regulates the permitted quota for agarwood export in order to sustain agarwood existence, and yet, India, in particular, has not been able to meet the quota because it has become more difficult to collect agarwood from its natural habitat because they are dissapearing.

Due to a significant increase in agarwood demand and high prices of agarwood, efforts have taken places to implement technology for stimulating agarwood production artificially, for a much faster process. Traditional wisdom combined with scientific knowledge have been implemented with numerous approaches to find the most efficient agarwood induction technology that will be able to fulfill the demand and at the same time conserve the remnants in the wilds.

This website provides a general overview of agarwood with specific reference to Inda as one of the most important country for agarwood production. Because the future of agarwood is dependent upon conservation and sustainable production management strategies, emphasis is given to research and development of induction technology for sustainable production of agarwood which is the main target of us – the Production and Utilization Technology for Sustainable Development of agarwood.